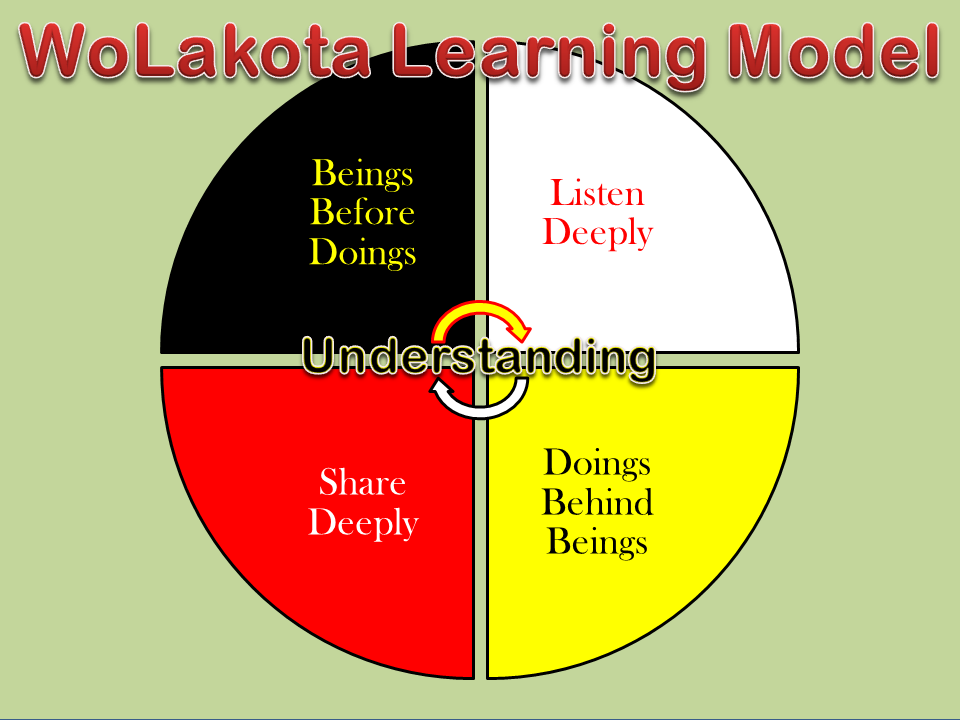

The WoLakota Learning Model reminds us:

- Beings are placed ahead of Doings

- Listen deeply to a Being to come to know that Being by his or her own definitions

- Doings (the naming, the stories, the values, accomplishments, etc. of others) are heard and appreciated as the wisdom of fellow Beings

- Sharing deeply the truth of my own Doings (names, stories, values, accomplishments, etc.) comes in response to deep listening and with the goal of mutual understanding

“Seek first to understand, then to be understood.” — Stephen R. Covey

“Opening yourself to another worldview will assist you in understanding what occurs both in and outside of native communities.” –Lakota Elder Dottie LeBeau

A Learning Model That Eliminates Potential Tension

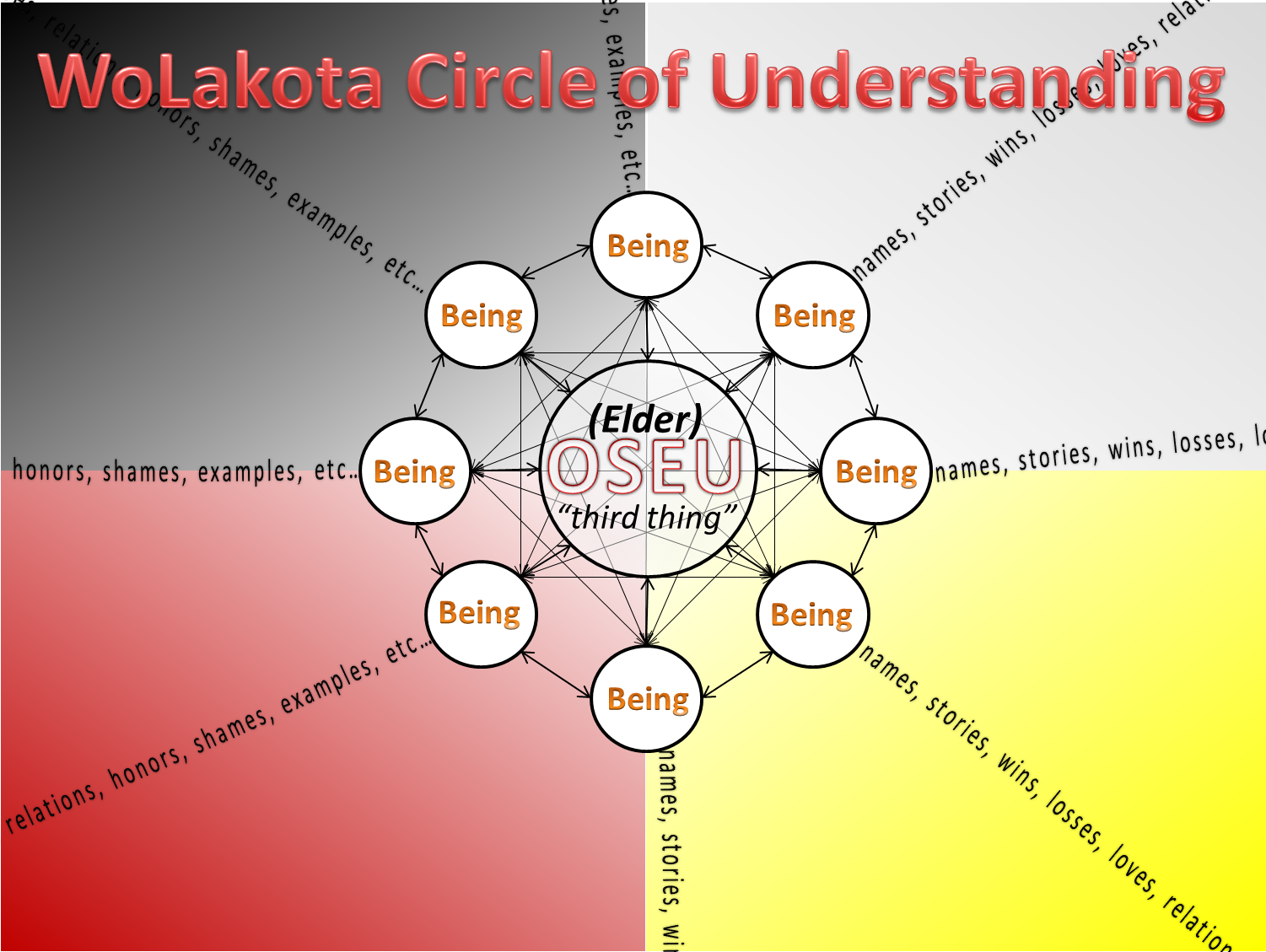

Sometimes, cultural work such as the work of the WoLakota Project creates tensions among both Native and non-Native teachers and students (Lars Anders-Baer, et al. 2008). To clarify, Native teachers sometimes feel uncomfortable with the idea that teaching about their culture and language is required of non-Native teachers in South Dakota. Conversely, non-Native teachers often feel uncomfortable trying to somehow do justice when teaching about a sacred culture and language like that of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota people. Most of these tensions derive from an outdated Western model of teaching and learning that mis-defines all “good teachers” as “experts” in a content of study. Most SD teachers are NOT “experts” in Lakota/Dakota/Nakota culture and language. However, in the WoLakota Project Learning Model, and consistent with most indigenous learning models, every person within the classroom – including the teacher – becomes a learner engaged around the content (the OSEU).

Two types of learning are prevalent within the WoLakota Project – Informational Learning and Transformational Learning. Informational Learning occurs as learners engage with the wisdom of the Elders through videos and resources. This is where students and teachers Learn About the culture and language, factual learning, where things such as ceremonies, language and ways of living are discovered, and knowledge is gained. For example, Elder Stephanie Charging Eagle (see her OSEU Four interview here) refers to a Hunka Ceremony as being something similar to a marriage – the taking on of a family member who is not a blood relative. Learners develop an understanding of the Hunka Ceremony by listening to the elder and through further research. In general, the WoLakota Project “Learn About” questions are designed as a starting place for this type of learning.

Transformational Learning happens as the learners reflect upon how what they experience is connected to their own lives. Stephanie refers to a Hunka relationship as “sacred.” Learners can then reflect on sacred relationships in their own lives and what makes them sacred. In this way, no teacher must be seen as an “expert” and the focus is placed on learning together. In a learning community setting– often a circle– the WoLakota Project “Learn From” questions are designed to spark this type of learning.

It’s important for teachers to share with their communities how learning will take place around the OSEU. Parents and community members can misinterpret the work with the OSEU as non-Native teachers coming in to try to teach Native students about their own culture. Families and community members must be made aware that all OSEU work has been guided directly by the Elders to provide opportunities for students, Native and non-Native, to develop understanding of themselves and their neighbors. The WoLakota Project works to bring understanding to all communities and individuals in South Dakota. It promotes the idea that we are all neighbors needing to understand one another for healing to take place.